7 September 2021

Figures taken from the Threatened Species Recovery Strategy. All images: Canva NFP.

Commemorated on 7 September since 1996, National Threatened Species Day may well be considered a day of mourning for our endangered species.

Of course, the aim of National Threatened Species Day, and of species-level conservation overall, is to halt, and even reverse, the decline in biodiversity and to shine a light on those species that need our help – which makes the date chosen, marking the death of the last known thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) in a Hobart zoo, a sombre one for a national day.

‘Benjamin’, as he was known, sadly died of hypothermia in 1936, the last of a species hunted to extinction. However, as the years go by and the threatened species count continues to track upwards – many still without national recovery plans and many more largely unnoticed by the Australian public – it seems we’ve learned little from our past.

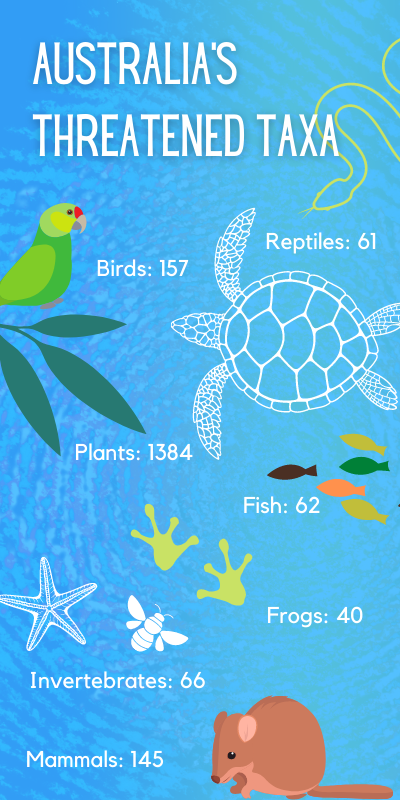

Worse, the plight of most of the 1,915 taxa recognised as threatened under the Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999), from the green turtle to the malleefowl, has our thumbprint (or oversized carbon footprint) all over it.

Lack of funding makes many efforts ‘Toothless Tigers’

On 21 May 2021, the Federal government released its Threatened Species Recovery Strategy 2021–2031 for the next decade. The strategy aims to identify areas of focus to support the recovery of threatened species and foster hands-on, real-world change through identifying priority species and communities, establishing concrete actions to recover them, and setting measurable targets.

Wildlife Queensland remains sceptical that the funding and forward momentum to address the issue will be found long-term, especially given ongoing attempts to further weaken environmental laws. However, an August 2021 study published in Ecology and Evolution recently compiled ‘the first complete, validated, and consistent taxon-specific threat and impact dataset for all nationally listed threatened taxa in Australia’ based on the IUCN Threat Impact Scoring System.

The data turned up 4,877 unique taxon–threat–impact combinations. ‘Habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation’ was the most prevalent combination, affecting 1,210 taxa, whereas a further 966 were affected by ‘invasive species and disease’. However, when assessing only high-impact threats or medium-impact threats, ‘invasive species and disease’ was, unsurprisingly, the most common combined threat.

While we hope that this comprehensive dataset will inform biological conservation and make adhering to the Threatened Species Recovery Strategy easier, the government still needs to address ongoing threatening processes and that less than half of the species listed under the Act currently have binding recovery plans in place.

Even our icons aren’t safe

Sure, we can add a little sweetener to National Threatened Species Day with the fluffy Threatened Species Bake Off. For researchers who are mired in the daily struggle to conserve biodiversity in this country, the cake-fest is a welcome reward and an opportunity to present some of their work in a more palatable way. But the truth is that unless they inspire real commitment in decision-makers, cute animal cakes are the empty calories in the recipe for disaster that is the current ”Threatened Species Die Off’.

So dire is Australia’s extinction crisis that not even the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) is safe. The EPBC Act lists the combined populations of koalas throughout Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory as threatened, and a Draft National Recovery Plan for the Koala (Combined Queensland, New South Wales and ACT Populations) is currently available for consultation and review.

Since so many of our human activities have contributed to koala decline, community engagement is one of three objectives included in the recovery plan for this species. The others are increasing population size and distribution in places where declines are predicted, and maintaining or improving factors that affect metapopulations, such as dispersal, gene flow and habitat degradation that reduces the size or viability of koala populations.

In response to the draft plan, WPSQ’s Fraser Coast Branch president expressed her disappointment that it failed to include the Fraser Coast region.

‘Our once-thriving Fraser Coast koala population appears to have crashed in recent years. A decade ago, wildlife rescuers in the region reported handling more than 50 koalas a year,’ stated Vanessa Elwell-Gavins. ‘But when our Branch conducted community koala counts over two successive years in 2014 and 2015, we were dismayed by the low numbers of sightings and the decline from 18 to 5 koalas between the two counts. Since 2015, only occasional and anecdotal sightings have been reported.’

Helping to arrest koala decline

The Fraser Coast branch hopes to undertake a further community koala count in 2022. Similar surveying and counts are currently being conducted on private property near Beaudesert, with the support of Wildlife Queensland’s Scenic Rim Branch and the Logan Valley Koala Project, and in the Logan Local Government Area from October to November 2021.

Wildlife Queensland will be working closely with Logan City Council to host a community webinar on koala spotting and surveying techniques in our popular Talking Wildlife series on 28 October 2021, with an iNaturalist citizen science survey to follow. Those in the Logan LGA are already being urged to report koala sightings.

Private property might soon prove the last bastion of security for koala populations, both in the south-east and further north on the Fraser Coast, as it is for other threatened species like the yellow-bellied glider and greater glider.

‘We have been interested to learn about the University of Queensland’s koala rehoming project on a large private property in the Fraser Coast area, with koalas from Tinana or Hervey Bay rehomed following injury or illness,’ Elwell-Gavins adds. ‘Unless land-clearing for development, mining and agriculture is terminated immediately, this rehoming might be these koalas only hope, because it is clear that human and koala populations cannot cohabit successfully.’

Lessons from history

Images: Canva NFP

Unfortunately, robustness, fierceness, fascinating marsupial lifestyles and even fluffy faces aren’t good indicators of species longevity. At the time of European settlement, the thylacine was Australia’s largest marsupial carnivore. That title now falls to its marsupial relatives in the order Dasyuromorphia: on the mainland and here in Queensland, the spotted-tailed quoll (Dasyurus maculatus), and in Tasmania, the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii).

Both south-eastern mainland subspecies of the spotted-tailed quoll are endangered under the EPBC Act (1999), as is the Tasmanian devil. Yet, despite even the scourge of devil facial tumour disease, there is still no national recovery plan for the devil. Recovery plans for many endangered species have stalled due to data deficiency or disagreement over the best way forward. And while there is a National Recovery Plan for the spotted-tailed quoll, territory loss for development is an ongoing issue for this species, which has already seen some 70% of habitat within its historical range fall to land clearing. Even so, peri-urban development continues largely unabated.

If we have learned a lesson from the thylacine, it is that failure to act is acting to fail. If we cannot engage the Federal government in committing to increased funding for programs to save species that are related to the now-extinct thylacine and face similar existential threats, consider how difficult it is to drum up support for lesser-known threatened fauna, such as native rodents, insects, invertebrates, marine turtles and reptiles, and particularly for endangered native flora.

Flora makes up the largest cohort of threatened species under the EPBC Act. Still, a recent study published in Biological Conservation, based on research conducted by the Threatened Species Recovery Hub, found that two-thirds of our native threatened plants aren’t even being monitored!

How you can help

You can view and comment on draft recovery plans and lobby the government to take action. National recovery plans are binding – once they are in place, the Federal government must act on their recommendations. Currently, draft plans are available for comment for the koala (until 24 September 2021) and the endangered eastern bristlebird (until 17 December 2021). Both of these species are threatened by habitat loss and increasing urbanisation, as well as climate change, invasive species, and disease.

You can also join our Quoll Seekers Network, donate, and subscribe to our free eBulletin to be kept informed about our upcoming Koala webinar and other relevant conservation news.

Of course, baking a cake or sharing a social media meme or your favourite photograph of an endangered species is still a significant, albeit small, way to get involved. But we will need large-scale, long-term actions and investment from Federal and state governments if we are to make National Threatened Species Day a cause for future celebration and not mere commiseration or commemoration for species we have already pushed to the very edge of existence or beyond.

Related articles and information: