The Mt Emerald wind farm in North Queensland. Images: Josh Bowell (greater glider); Steven Nowakowski (Mt Emerald wind farm).

22 December 2023

Wind power is an integral part of the energy mix for the global transition to a cleaner, more sustainable future. However, it could seriously affect our ecological systems and threatened species if inappropriately located and insensitively developed.

Queensland’s transition to clean energy has grown from approximately 3.2% of Queensland’s total generation in 2005 to about 26% of total generation in 2023. Of this 26%, 3.3% is sourced from wind generation.1

The Queensland Government has recently announced a revised renewable energy target of 75% by 2035. The government’s Renewable Energy Zones initiative will involve more wind developments to achieve this goal.

Wind farm locations

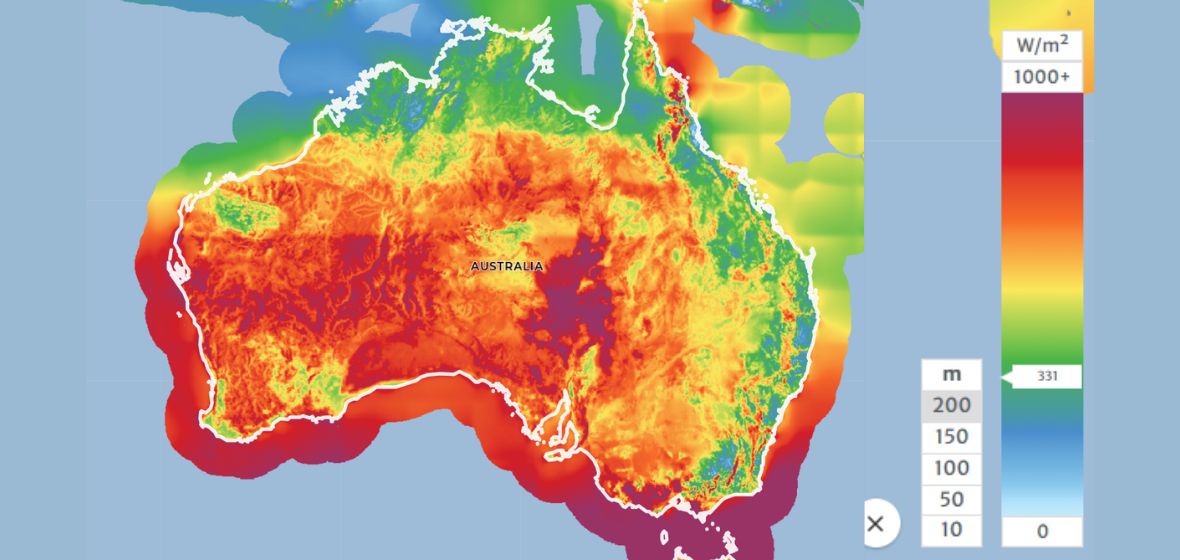

While Australia has some of the best available wind resources in the world, they are predominantly located in the southern parts of the country, and mapping shows the greatest wind potential lies in the coastal regions of West, South West, South, and South East Australia.

This is depicted in Figure 1, which shows the highest power density from wind resources concentrated around the southern half of Australia.2

Figure 1: Australia’s wind resources are depicted as mean power density and expressed as W/m2. Global Wind Atlas version 3.3.

Except for isolated locations along the ridges of the Great Dividing Range, Queensland does not boast outstanding onshore or offshore wind resources compared to Australia’s southern states. Using the most basic resource test, Queensland’s suitability for wind farm development appears somewhat questionable.

In Queensland, many of these limited locations marked for large-scale wind farm projects contain biodiverse remnant forests that are often the habitat of threatened species, including the greater glider (Petauroides volans), koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), spectacled flying fox (Pteropus conspicillatus), Sharman’s rock wallaby (Petrogale sharmani), and the red goshawk (Erythrotriorchis radiatus).

Environmental impacts of land clearing

The large footprints associated with wind farms result not just from the turbine towers and footings (typically, a 2ha cleared area is required per tower) but also from the access roads, which need substantial widths to enable the transport of tower sections, blades (some over 85m in length), gearboxes, and nacelles.

Many more wind farm projects are proposed, approved, or under construction throughout Queensland, including Chalumbin, Lotus Creek, Stony Creek, Gawara Baya, Mt Fox, Desailly, Clarke Creek, and Moah Creek. Due to land clearing activities, numerous projects carry the potential for negative impacts, such as habitat disruption and the displacement of species.

The approved projects in Queensland are set to result in the clearance of tens of thousands of hectares of remnant forest. If all wind farms receive approval, the extent of clearance is expected to increase significantly. Additional edge effects and fragmentation outside the initial clearing will be experienced, and these associated impacts are poorly understood.

Understanding the impact on greater gliders

Ecological field surveys of planned wind farms have revealed potential negative impacts on threatened species around Queensland, such as the endangered greater glider. Impacts include:

- habitat loss and fragmentation

- noise and vibration

- collision risks

- electromagnetic fields.

However, despite these concerns, a number of projects have recently been approved in Queensland. Some projects, including the Stony Creek, Lotus Creek and Chalumbin wind farms, impact the greater glider. For example, the ecological assessment report for the approved Chalumbin Wind farm, recently renamed Wooroora Station Wind Farm, observed a total of 64 greater gliders across the project area.3

A wind turbine development at Lotus Creek in Central Queensland has recently been approved. The southern section of the development site is characterised by a very high number and range of hollows, supporting a rich biodiversity that includes several threatened species. Greater gliders were recorded at 131 locations within the development site across all survey periods.4

Furthermore, on 7 December 2023, approval was still granted for the Stony Creek wind farm in South East Queensland even though the ecological assessment report stated that the proposed land clearing would adversely impact the endangered greater glider: “The removal of 179.2 ha greater glider foraging habitat is regarded as an adverse impact to habitat critical to the survival of the species. Therefore, it is likely that the proposed development will result in a significant impact to the greater glider.”5

Mitigating the impact of wind farms

The Queensland Department of Environment and Science is reviewing the Wind Farm Code (State Code 23) and guidelines used in the planning assessment of wind farm applications. One key proposed change aims to strengthen the environmental assessment criteria to prevent impacts on threatened species and associated habitats and areas of high ecological value.

Wind farm developers in Queensland are responding to concerns by implementing measures to reduce harm to wildlife. These include:

- careful site selection

- radar use to detect birds

- shutdowns during migration periods

- the use of deterrent devices.

The relocation of affected wildlife can protect endangered fauna and involve the rehoming of affected individuals in similar vegetation. Land clearing mitigations include offsetting when a developer commits to retaining or establishing equivalent vegetation communities. Wildlife Queensland has major concerns about offset policy and its implications, especially given the challenges in replacing hollow-bearing trees, essential habitats for native species such as greater gliders.

Considering previously cleared land

Wind farms have an advantage over other forms of renewable energy, such as solar and hydroelectric, in that they can more easily co-exist with other land uses. Their “footprint” is predominantly in the vertical plane, leaving cleared areas largely available for other purposes, such as agriculture, beneath and around the turbine towers.

While their footprint is only one factor in determining the most appropriate location for a wind farm, it seems more logical to site wind farms in areas that have already been cleared rather than affecting untouched areas.

Should we be clearing and fragmenting forests for renewables?

Decarbonising our electricity sources is necessary but must be carefully considered to reduce overall environmental effects. It should not introduce a myriad of new environmental problems while only solving one.

It might be considered ironic that we’re clearing away trees, which naturally capture carbon, to construct energy-producing wind farms that have a limited impact on reducing our carbon emissions.

“Wildlife Queensland supports the construction of wind farms to facilitate the move to renewable energy but only if appropriate sites do not threaten our national heritage and create havoc for our wildlife,” says Wildlife Queensland’s Policies and Campaigns Manager Des Boyland.

“Unfortunately, recent government approvals have shown complete disregard for our wildlife and its habitat. Governments will only listen when the broader community speaks out. We need your assistance.”

While wind power is part of the energy mix for a sustainable future, careful planning is essential to prevent harm to threatened species such as the greater glider. As the state navigates the transition to renewable energy, we must address the impact on our precious wildlife before it’s too late.

How you can help

- Have your say: Contact the Federal Minister for the Environment and Water, Tania Plibersek, your Queensland Minister for the Environment and the Great Barrier Reef, Minister for Science and Innovation, Leanne Linard, and your local MP to voice your concerns.

- Donate to help fund our new greater glider project, investigating behaviour and habitat preferences so we can take proactive measures if their habitat is pressured or destroyed.

- Report a glider sighting: Records of sightings can be instrumental in the decision on development locations.

- Read Wildlife Queensland’s ‘A Revegetation Guide to the Threatened Gliders of Southern Queensland’ to learn about the habitat needs of Queensland’s two largest gliding marsupials — the greater glider and the yellow-bellied glider — and what you can do to help them.

References:

- Queensland Government Department of Energy and Climate. (Last updated: 12 December 2023). Queensland’s Renewable Energy Targets. Retrieved from https://www.epw.qld.gov.au/about/initiatives/renewable-energy-targets

- Global Wind Atlas version 3.3. (n.d.). Wind Map of Australia: Mean Power Density. Retrieved from https://globalwindatlas.info/en/area/Australia

- Attexo Group Pty Ltd. (2023). Chalumbin Wind Farm Final Public Environment Report, Section 8: Significant Impact Assessment – Part 3 (24 pages). (p. 479). Retrieved from https://arkenergy.com.au/documents/1291/Final_PER_-_Section_8.0_Significant_Impact_Assessment_Part3_24_pages_si2uV5h.pdf

- NGH Pty Ltd. (2021). Preliminary Documentation 2020/8867 Lotus Creek Wind Farm, p. 188. Retrieved from https://arkenergy.com.au/documents/976/LotusCreekWF_EPBC_PreliminaryDocumentation_Part1_Report_225pages.pdf

- Pavitt, A., & James, A. (2022). Stony Creek Wind Farm Ecological Assessment Report, p. 105. Retrieved from Project Decision · EPBC Act Public Portal website: https://epbcpublicportal.awe.gov.au/all-referrals/project-referral-summary/project-decision/?id=a69220cb-fe4f-ed11-bba2-0022481867a5