Author: Rachael Harris

South-eastern Queensland is in the midst of a very hot and very dry period. Data accessed on the Bureau of Meteorology website shows the total rainfall for Brisbane from January to November 2019 was only 438mm. The 2018 total rainfall for our capital city was 859mm, 15% lower than the long-term average rainfall of 1011.5mm. Brisbane’s mean daily maximum temperature (Jan-Nov) was 27.4 °C, which is 0.4 C° above the long-term annual average. There is very little to indicate the remainder of December will provide good rainfall or lower temperatures; it seems Brisbane in 2019 is well on track to record another year of below-average rainfall and above-average temperature.

How has this affected our wildlife?

An industry placement student from the University of Queensland has been working with Wildlife Queensland and the Queensland Glider Network to monitor nest boxes installed within urban bushland in the Forrestdale area in Logan. The site is within the Flinders Peak to Karawatha corridor and the nest boxes have been monitored since 2011. Collecting repeat occupancy data for nest boxes over long periods helps to provide a better understanding of occupancy trends and environmental factors that may impact nest box occupancy by hollow-dependent fauna.

At this particular study site, the list of animals found to inhabit the boxes includes brushtail possums, squirrel gliders (most likely), native bees, honey bees and the occasional carpet python.

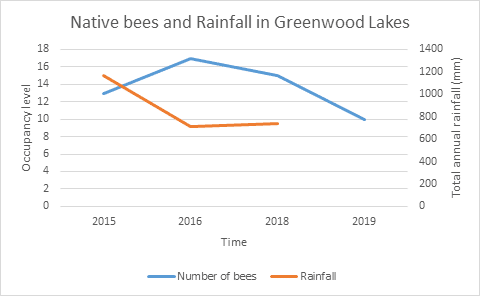

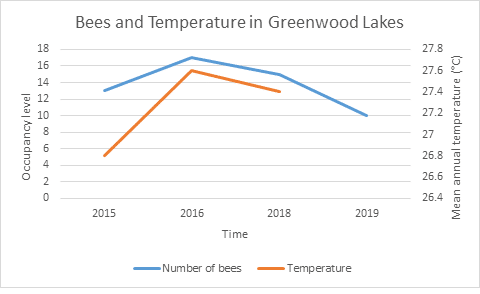

Analysis of this longitudinal data appears to indicate an overall decreasing trend in occupancy of nest boxes by brushtail possums and native bees during the period 2016 – 2019 inclusive. Inhabitation of nest boxes by native bees increased from 2015 to 2016 (31%) yet recorded an overall decrease in occupancy (41%) from 2016 through 2019 (Figure 5 & 6).

Figure 5: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of native bees from Greenwood Lakes against the total annual rainfall.

Figure 5: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of native bees from Greenwood Lakes against the total annual rainfall. Figure 6: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of native bees from Greenwood Lakes against the mean annual temperature.

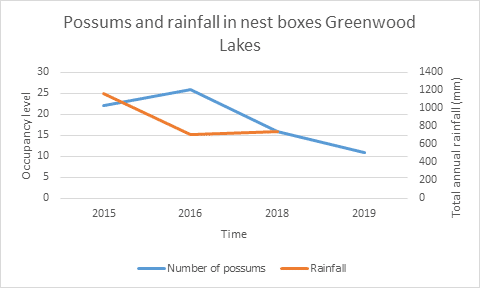

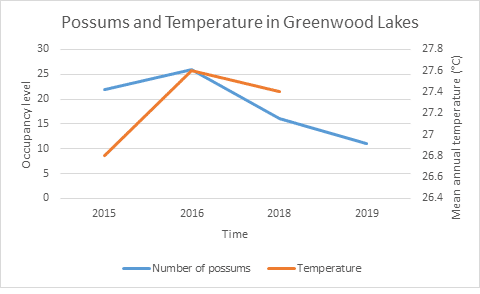

Figure 6: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of native bees from Greenwood Lakes against the mean annual temperature.Brushtail possums followed a similar trend to native bees, exhibiting a 58% decrease in nest box occupation between 2016 and 2019 (Figures 3 & 4).

Figure 3: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of possums from Greenwood Lakes against the total annual rainfall.

Figure 3: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of possums from Greenwood Lakes against the total annual rainfall. Figure 4: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of possums from Greenwood Lakes against the mean annual temperature.

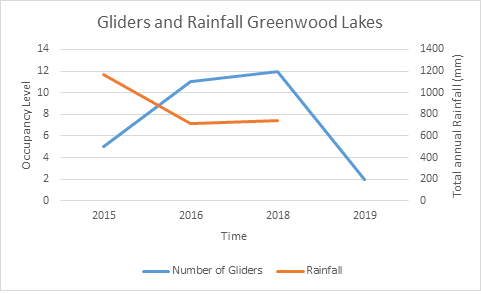

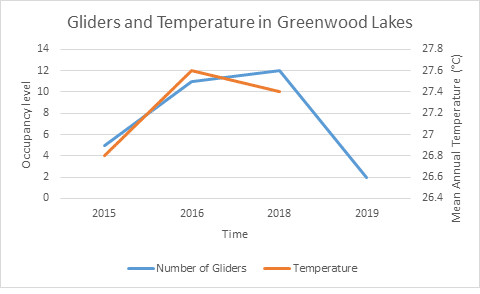

Figure 4: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of possums from Greenwood Lakes against the mean annual temperature.Frighteningly, the number of nest boxes occupied by gliders has decreased from 12 in 2016 to just two in 2019 (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of gliders from Greenwood Lakes against the total annual rainfall.

Figure 1: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of gliders from Greenwood Lakes against the total annual rainfall. Figure 2: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of gliders from Greenwood Lakes against the mean annual temperature.

Figure 2: Graph depicting the results of occupancy levels of gliders from Greenwood Lakes against the mean annual temperature.Could the current hot and dry conditions be behind this decreasing trend in nest box use by hollow-dependent fauna?

It doesn’t seem like an unreasonable summation.

Our data was examined alongside simple climatic data for mean annual temperature and total annual rainfall according to the Bureau of Meteorology (Archerfield weather station) and there appears to be a loose pattern. There is an overall decrease in total annual rainfall from 2015 to 2018 and an overall increase in mean annual temperature from 2015 to 2018. It’s not unreasonable to predict this will create a hotter, drier environment for our wildlife. In a study on drought and bees, Minckley et al. (2013) identified that as the number of flowering plants decreased as a response to drought, so too did the activity of most bee species.

So, it is certainly possible that our current hot and dry conditions can lead to a decrease in favourable conditions for gliders, possums and native bees through a reduction in resources such as pollen, nectar from flowering plants, insect numbers and water availability (Dierenfeld 2009; Minckley et al. 2013).

To present a balanced argument, a study conducted in New South Wales in 1987 found that glider populations appeared to be resistant to severe drought (Lunney 1987). However, there is no doubt that our local landscape has changed significantly in 30 years, much to the detriment of native wildlife.

An animal’s ability to cope with climatic extremes may be grossly limited under the weight of compounding threatening processes including habitat clearing, fragmentation, modification and introduced predators/competitors. Patch size and localised environmental conditions will certainly play a part in the ability of animal species to survive challenging climatic conditions. We could be witnessing the early impact of a hot and dry future climate scenario that these three species will be forced to live with.

Wildlife Queensland will continue to monitor these nest boxes and try to understand how a changing climate might affect glider, possum and native bee populations in local bushland reserves.

About the author: Rachael Harris was a University of Queensland placement student with the Wildlife Queensland Projects Team in 2019.

References

- Dierenfeld, ES 2009, ‘Feeding Behavior and Nutrition of the Sugar Glider (Petaurus breviceps)’, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 209-15.

- Lunney, D 1987, ‘Effects of logging, fire and drought on possums and gliders in the coastal forests near Bega, NSW’, Wildlife Research, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 263-74.

- Minckley, RL, Roulston, TAH & Williams, NM 2013, ‘Resource assurance predicts specialist and generalist bee activity in drought’, Proceedings. Biological Sciences, vol. 280, no. 1759, pp. 20122703-.

- Rowston, C 1998, ‘Nest- and refuge-tree usage by squirrel gliders, Petaurus norfolcensis, in south-east Queensland’, Wildlife Research, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 157-64.